Public Restroom to Public Healthroom

As part of GoInvo's Design Vision Series on Health Futures, we explore preventative health infrastructure for cities and towns.

Infrastructure is public health, preventive health, and personal health. Historically, we see this relationship in everything from the reduction of waterborne disease through water sanitation systems to the one-year extension to New York City citizens’ lifespan with added bike lanes.1 As healthcare shifts from a focus on treatment to prevention, from quantity to quality, and from mega-medical campuses to local community centers, new infrastructural opportunities continue to arise.

The Public Healthroom Concept

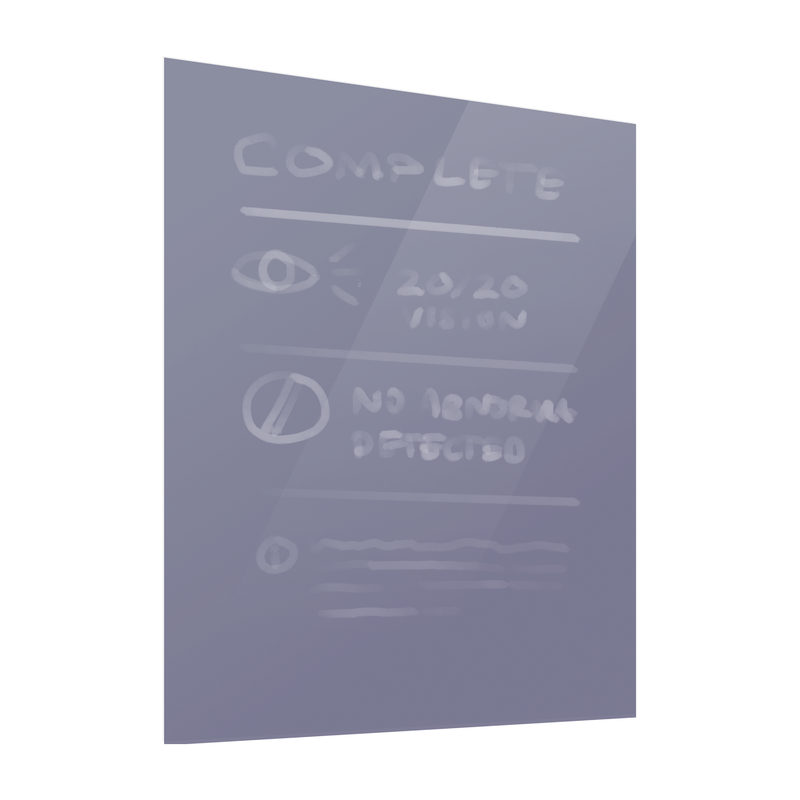

One such opportunity is the screening and prevention of chronic illnesses—specifically by evolving the role of public restrooms in health. The public healthroom is a one-stop shop for US residents to access basic health screening through daily encounters. The room is composed of devices and communication tools that provide screening and risk assessment for common chronic diseases like diabetes and heart attacks. These devices collect the resident’s biometric data to generate a personal health “receipt” that can indicate health abnormalities, suggest further testing, and provide useful information for follow-up with a primary care physician.

The public healthroom follows four primary principles:

- Residents own their health data. The public healthroom is a means for individuals to access and understand their key physical health indicators, but it protects your privacy and does not sell historical data to third-parties.

- All residents should have easy access to preventive care. No one should have to ignore health concerns because of geographic or socioeconomic barriers.

- Preventive care must meet residents where they are. The public healthroom bridges the gap between complete self-care and professional hospital care. Based on analysis of a resident’s biometrics across time, the healthroom provides detailed recommendations on seeking the appropriate level of care.

- Personal health is relative. The public healthroom helps each individual detect abnormalities in the context of their own history (e.g., sudden weight fluctuation, height loss, vision loss). Uncovering hidden signals can help prevent deterioration of various diseases (e.g., changes to the skin indicating risk for skin cancer).

Who benefits from a Public Healthroom?

Individuals

In 2015, only 8% of Americans age 35 or older received all high-priority preventive services recommended by providers, and nearly 5% received none. The year before, 60% of US residents had at least one chronic disease. (CDC)

Lack of preventive care use is a long-established issue in the US, and little has changed despite increased coverage through the Affordable Care Act. A 2018 survey identified lack of trust in physicians, long wait times, and work and family obligations as reasons for missing care (Borsky et. al, 2018). The public healthroom can provide residents with easy access to health screening and assistance as they attempt to navigate the complex healthcare system and receive necessary care.

Cities/Towns

Instead of being a strictly clinical effort, preventive primary care should be integrated into the community.

It is time to “shift delivery into the community, reaching people where they live, work, learn, and play.” (Krist et. al, 2015)

State/Federal Government

Responsible for setting data-driven national health objectives for the decade, Healthy People 2030 reported little progress when it came to increasing preventive care delivery and access. The target is to provide evidence-based preventive care to 11.5% of the population by 2030.2

Currently, it is at 6.5%.

How does the Public Healthroom help?

Health Screening as Daily Encounters:

- Conducts primary care checkups in adherence to state guidelines

- Provides each patient with a snapshot of their health

- Increases access to screenings and further assistance when necessary

Increase Awareness for Preventative Health:

- Informs individuals about next steps after health screening

- Promotes relevant, micro-lifestyle changes that could prevent illnesses

What should the Public Healthroom measure?

Exploring Health Futures: Public Healthroom Design Vision

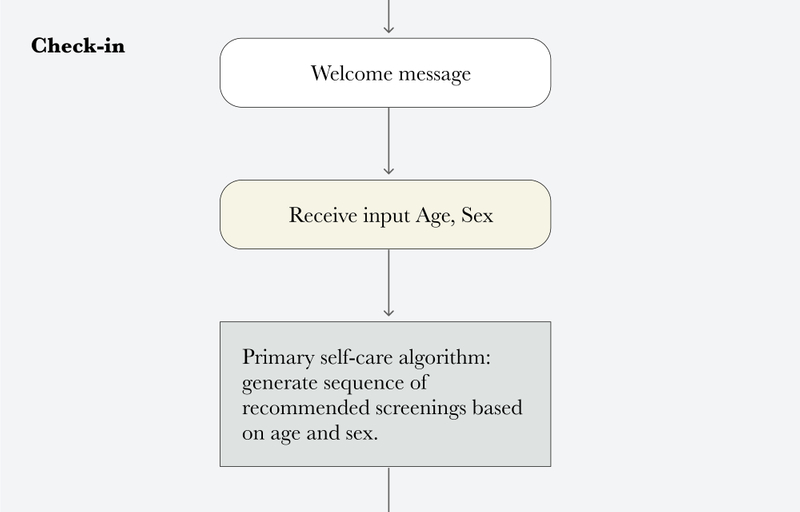

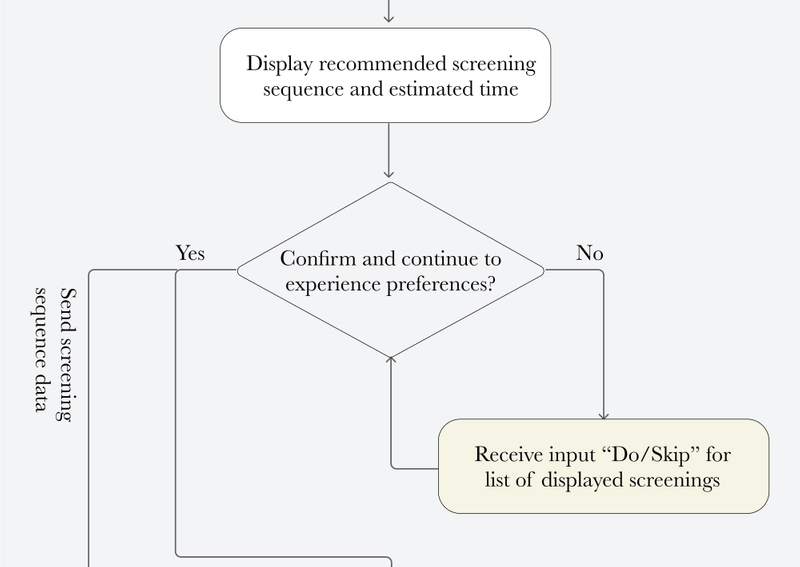

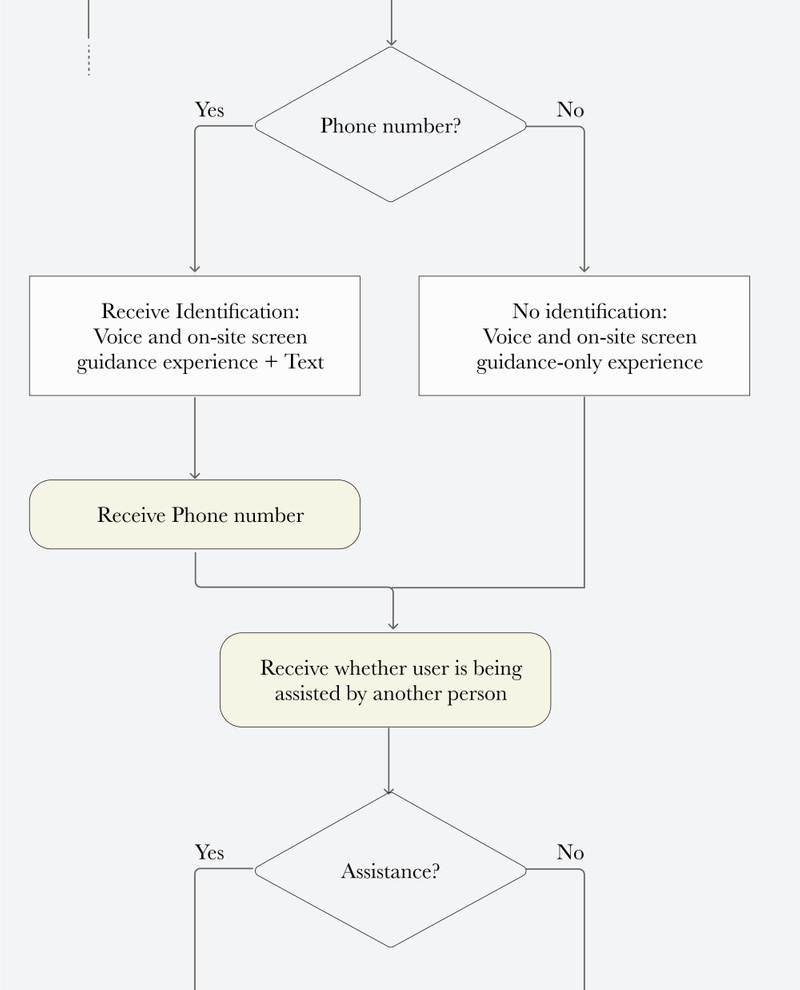

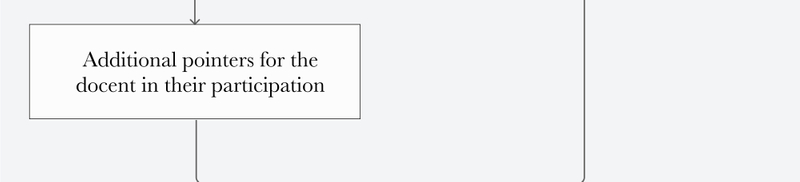

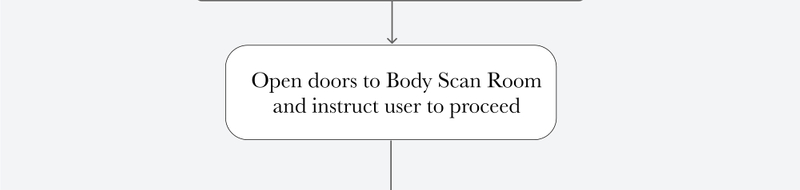

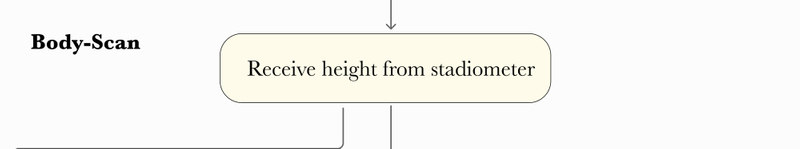

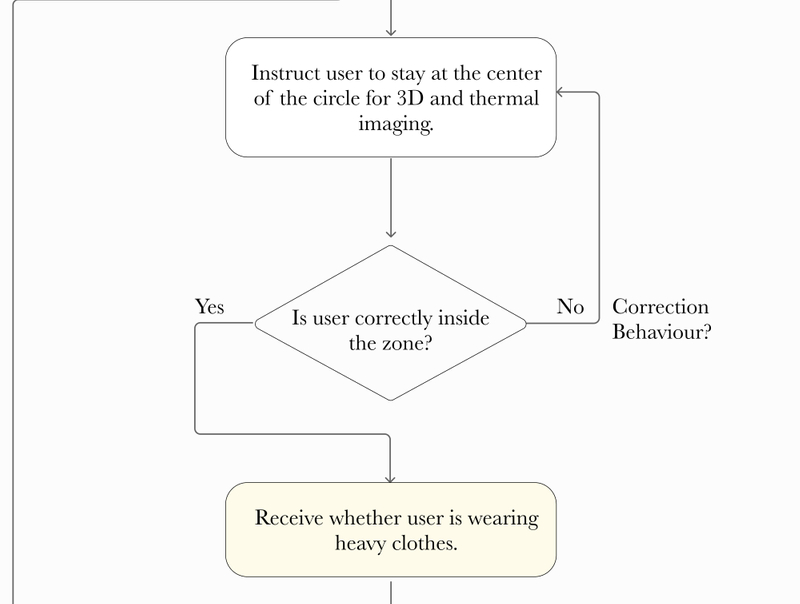

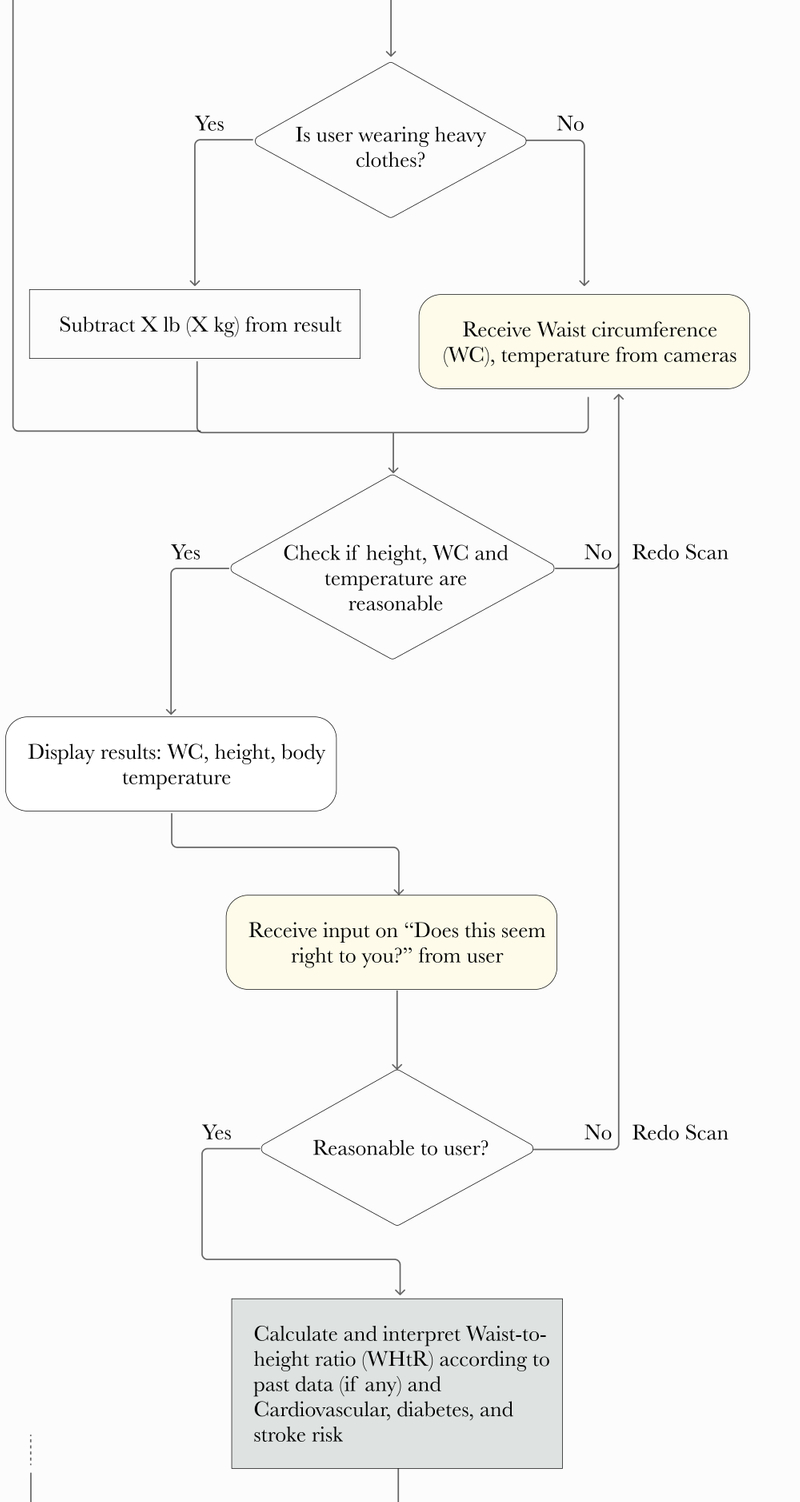

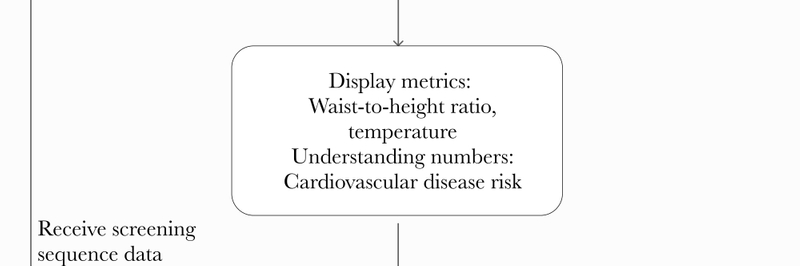

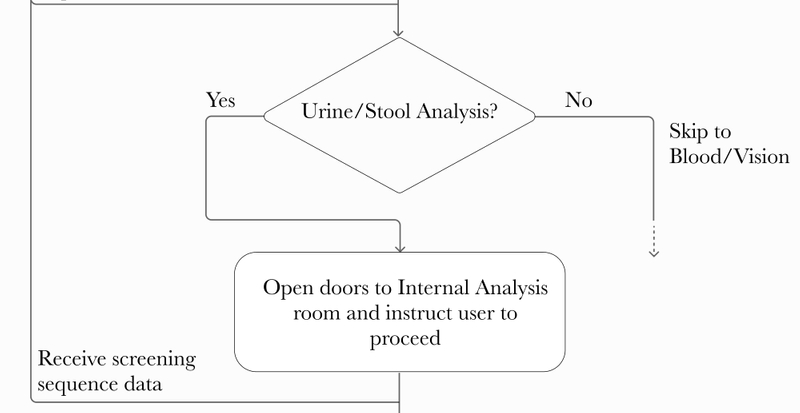

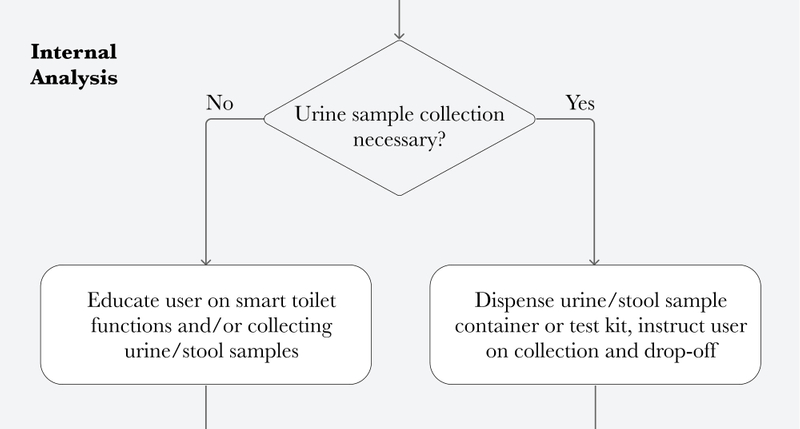

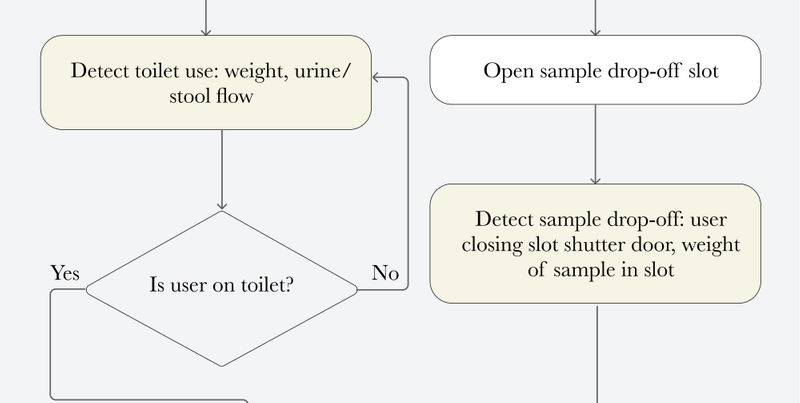

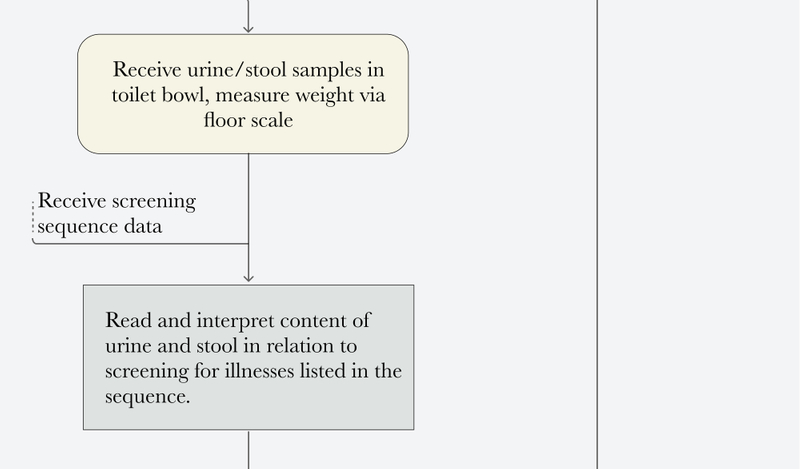

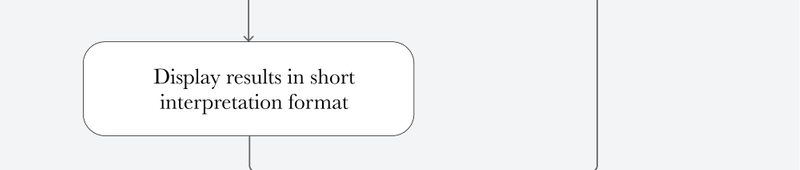

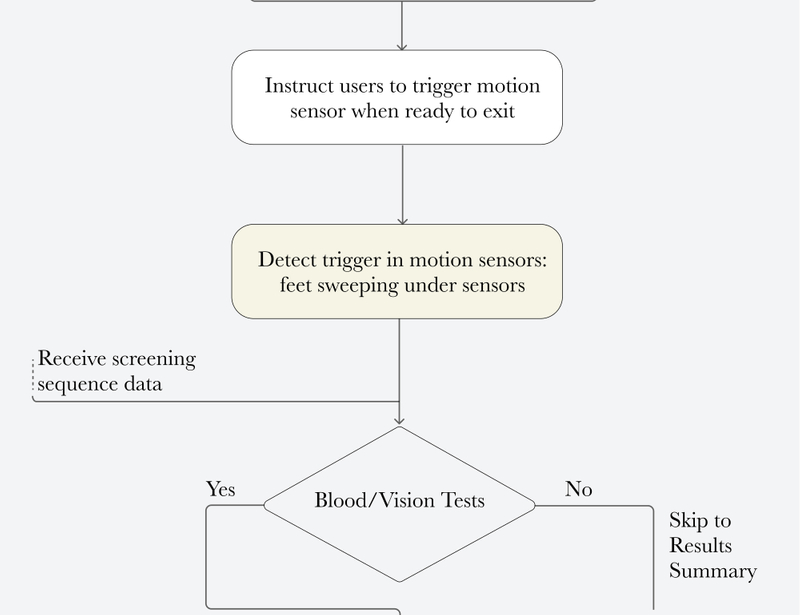

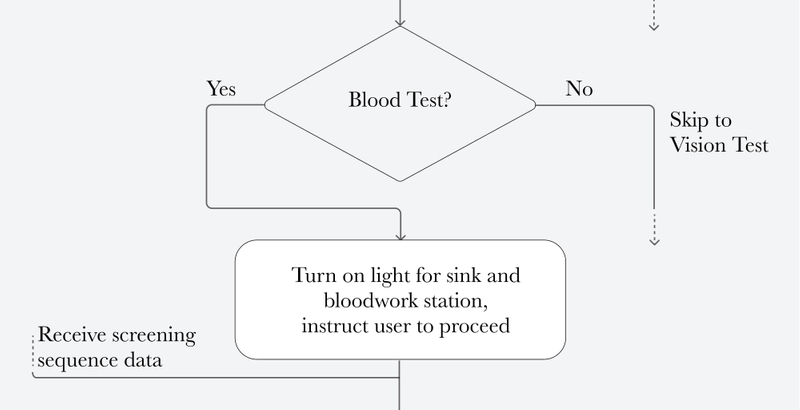

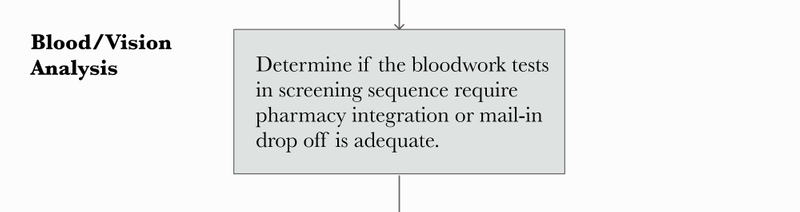

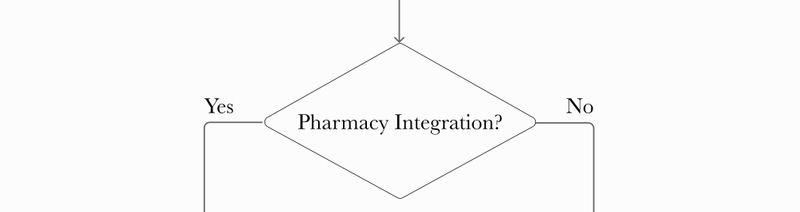

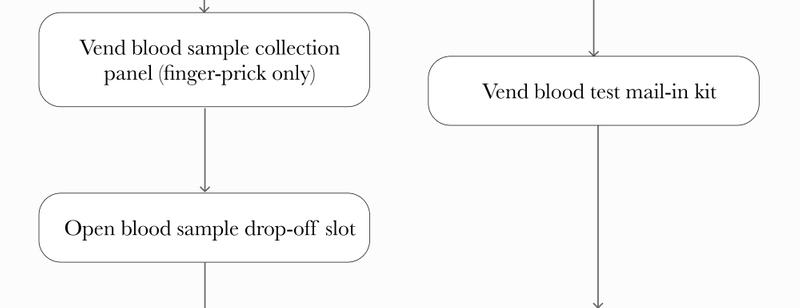

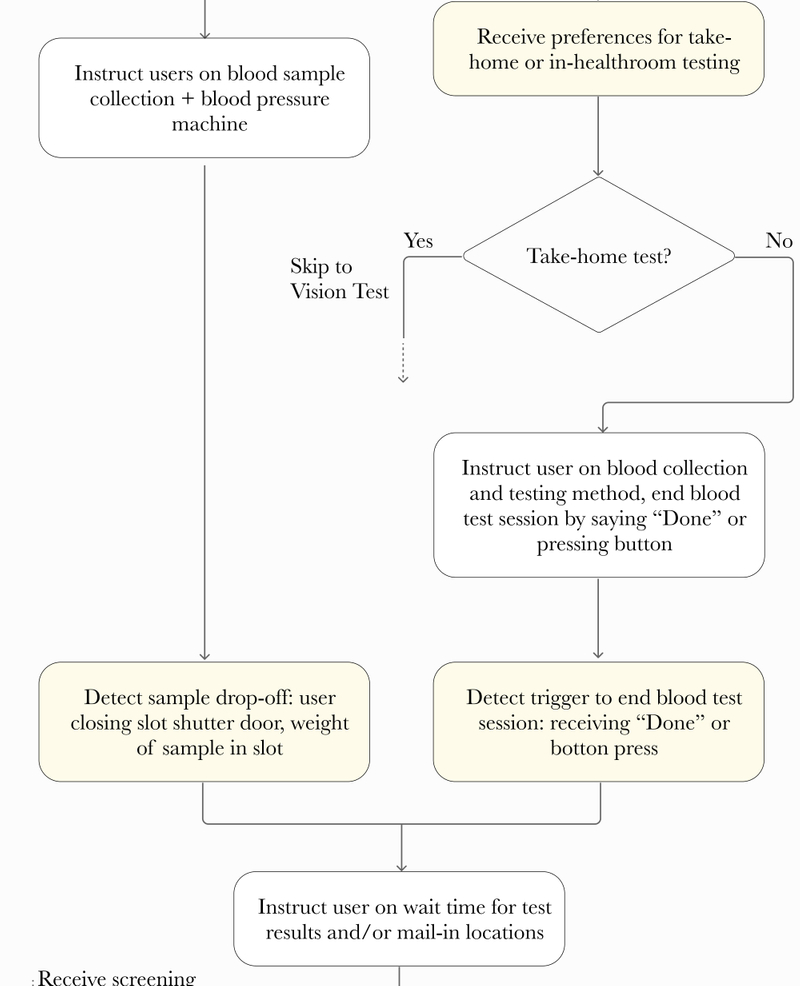

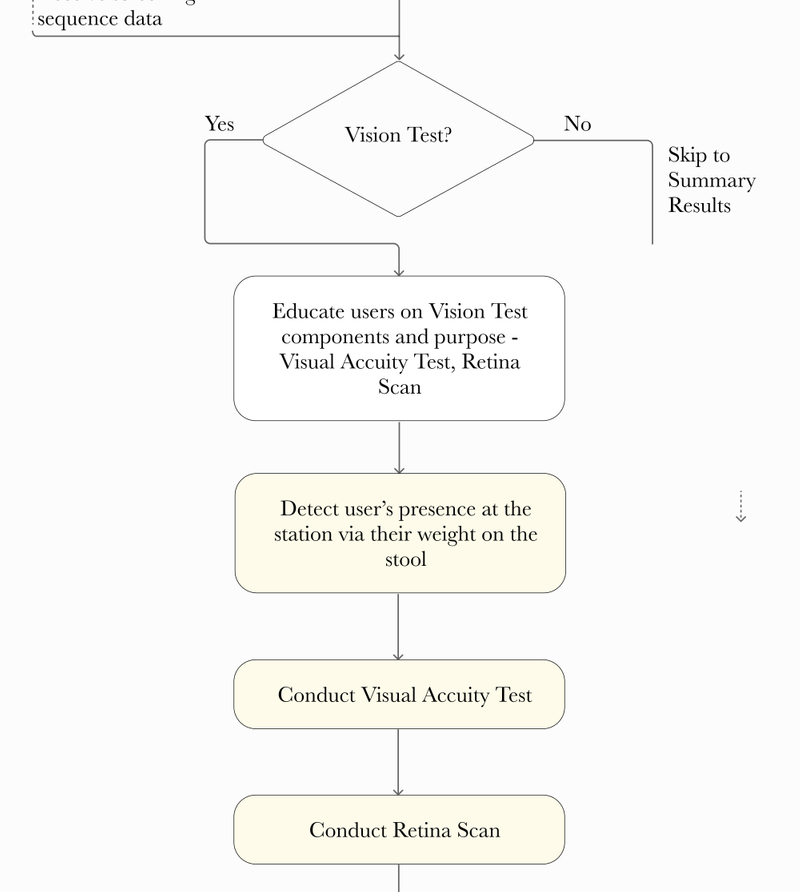

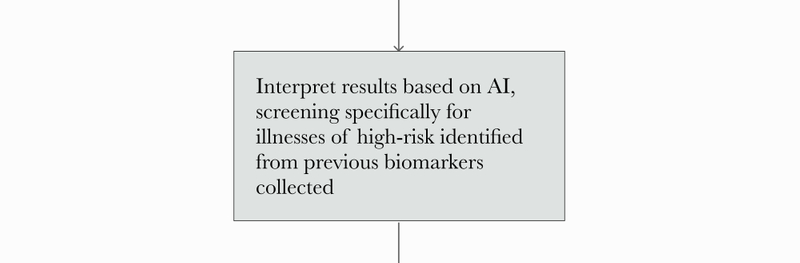

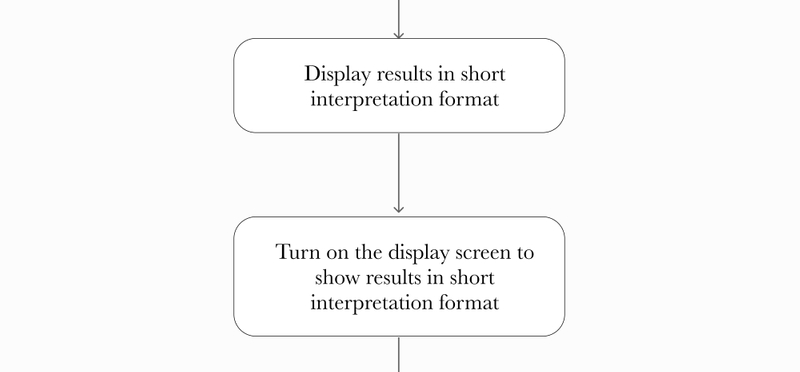

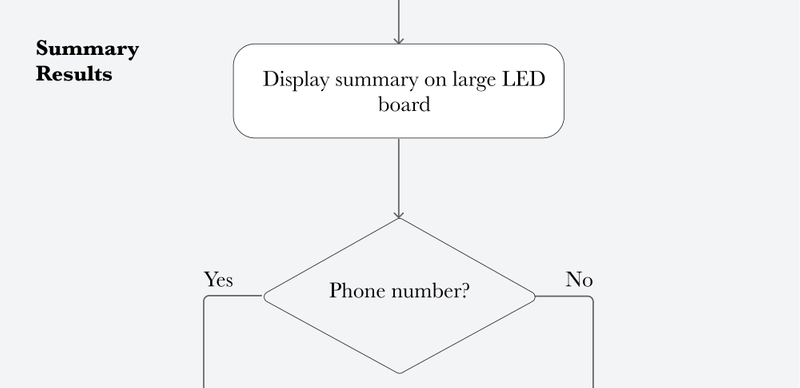

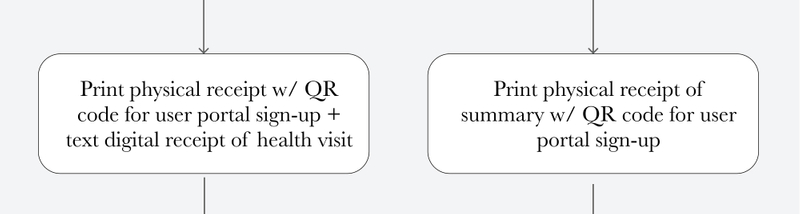

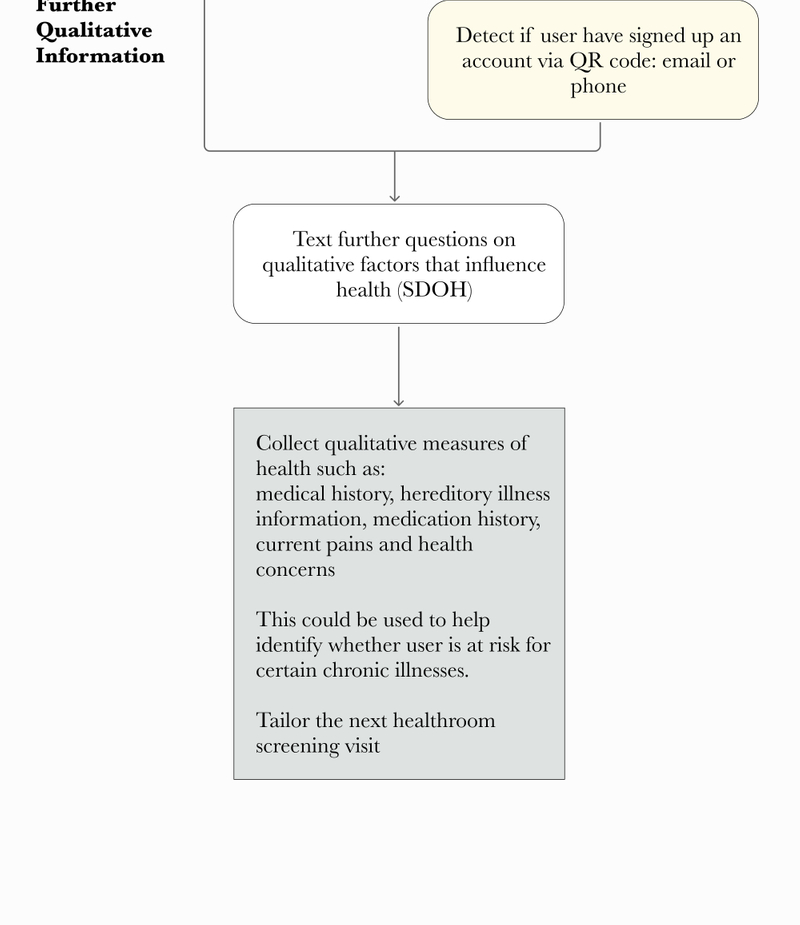

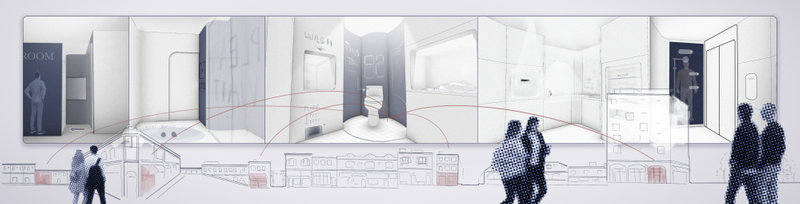

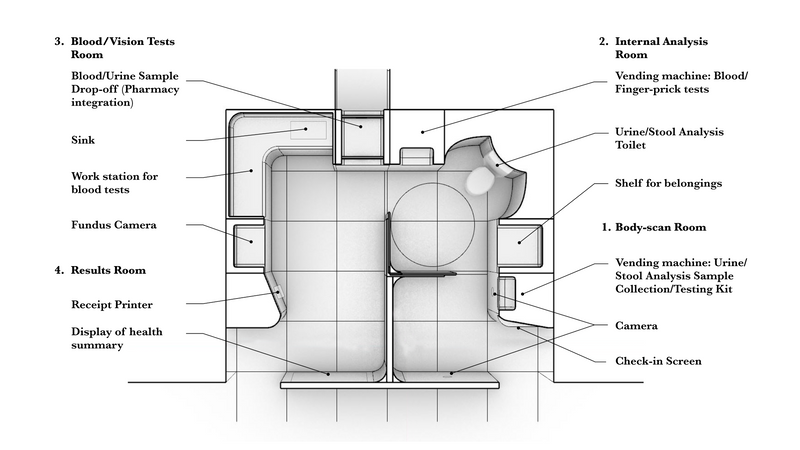

Among the various methods to accomplish measurement goals detailed above, the following is one possible version of the screening episode: a fully-guided, automated sequence. The room itself is built modularly, so components can be replaced after extended use or updated with newer technology. As a thought experiment, this focuses less on limitations and logistics and explores a futuristic, ideal experience.

Final Thoughts

In the fiscal year 2021-2022, the operation cost of San Francisco Public Works was $12.7 million or $113,000 per year per public portable toilet open 40 hours/week.3 With this as a baseline, the costs to engineer, build, and operate the public healthroom would be much higher—however, there is significant potential value in developing a preventive health infrastructure that transitions US healthcare spendings from quantity to quality. The next step would be developing a minimum viable product (MVP) with analysis on potential funding structures (private vs. public vs. hybrid).

One possible MVP approach is to develop the lowest-cost version that aggregates current off-the-shelf technologies but maximizes ease of use. Another is to develop each tool separately:

- Refurbish public or community center (YMCA, Student Centers, retail toilets) restrooms with urine/stool analysis toilets

- Develop a software for screening recommendations based on age and sex for retail healthcare (CVS MinuteClinic, Walgreens Health, Walmart Health Center), and integrating with their screening/lab test services

- Aggregate at-home test/finger-prick test vendors into one physical vending machine at retailers and community health centers

By promoting lifestyle changes and increasing preventive care awareness and access, policy makers and care providers are constantly striving to support better health outcomes for all—the Public Healthroom opens up a conversation around seamlessly integrating health into our daily encounters via the built environment. As emergent technologies develop and preventive care needs increase in the next five years, success in implementation and public utilization will rely heavily on design, and on how thoroughly we consider how the experience of engaging with one’s health can be seamless and timely without over-complications in technology.

Authors

Contributors

Samantha Wuu

Craig McGinley

References

- Bike lanes are a sound public health investment: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-costbenefit-bike-lanes/bike-lanes-are-a-sound-public-health-investment-idUSKCN11Z23A

- Healthy People 2030: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/preventive-care

- Two cities’ approaches to increasing public bathrooms: https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/two-cities-approaches-to-increasing-public-bathrooms/628387/