Closing the SNAP gap

for the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance

Problem

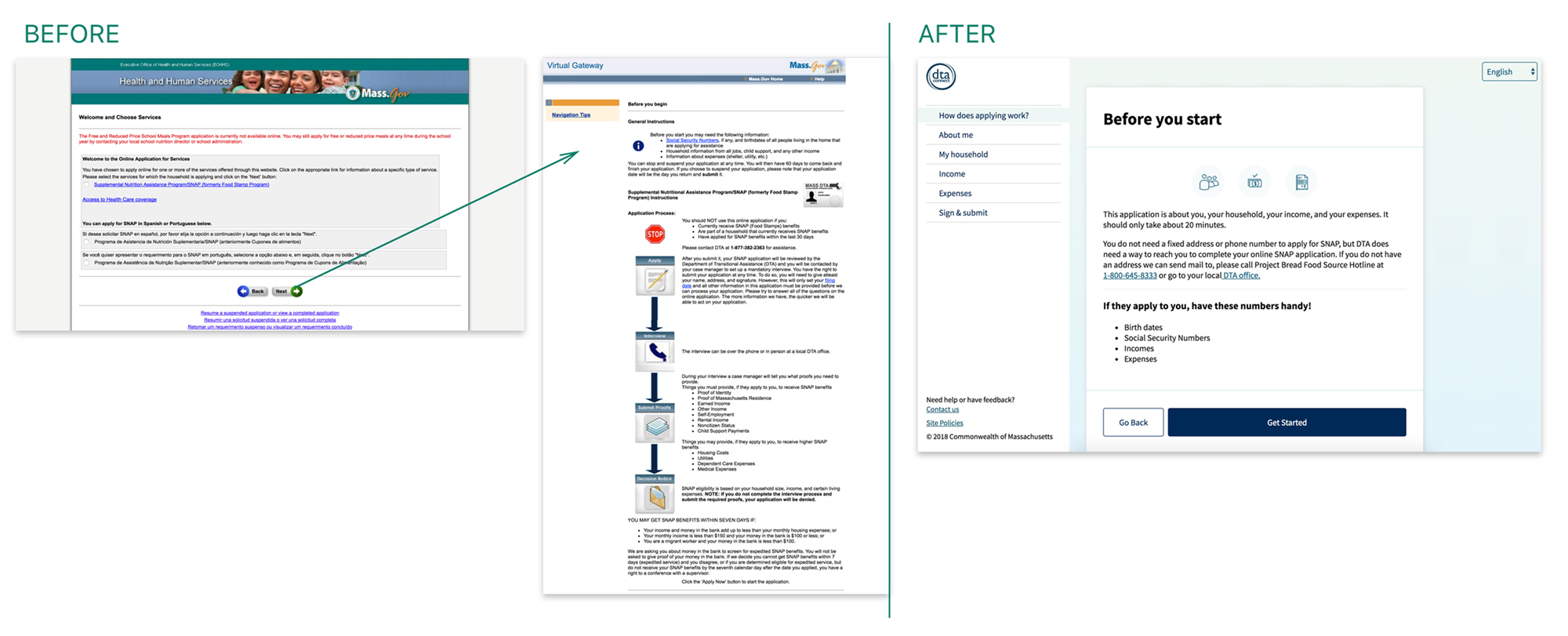

Food insecurity takes a significant toll on public health across the country. Tragically, one out of ten of households in Massachusetts is ‘food insecure’ (as reported by Project Bread) 1. The Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance (DTA) is hard at work to provide support for MA residents through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), but the application process for both staff and applicant is grueling. In 2017, a two-person family typically encountered 90 questions just to get past the first step.

Solution

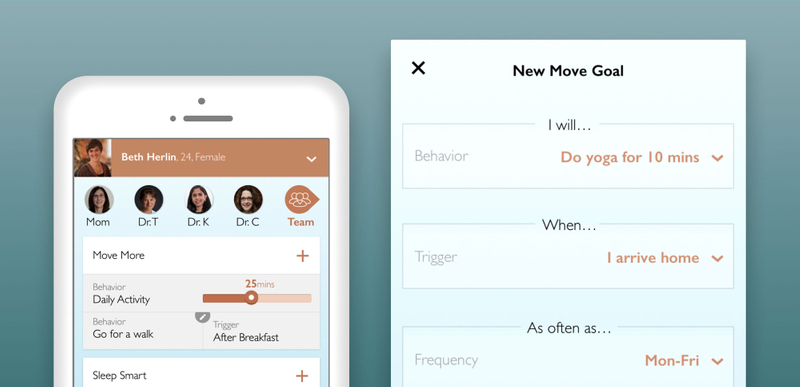

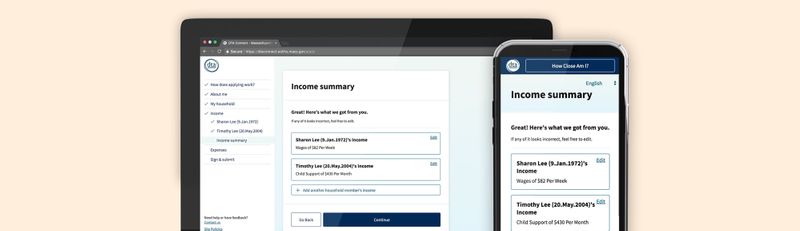

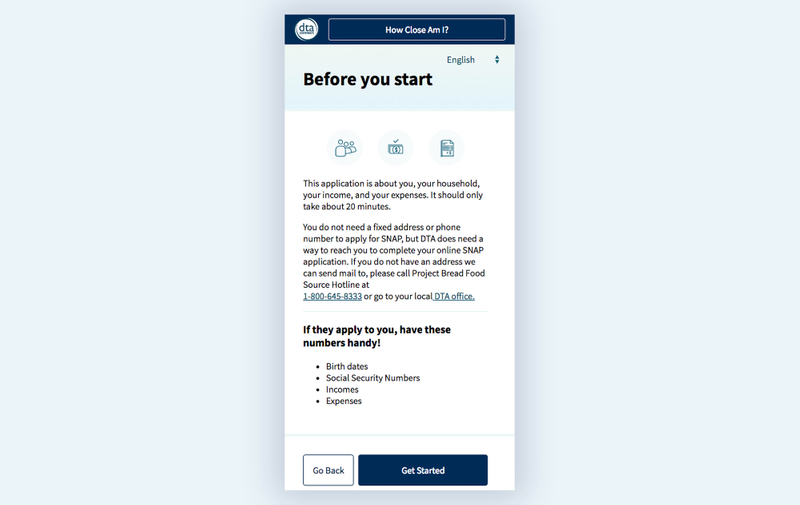

Our project aimed to make this first step welcoming rather than prohibitive through a redesign of the online application. The redesign, conducted by the trio of MA DTA, Conduent, and GoInvo, focused on a mobile-first, non-intimidating, accessible, and quick service with multiple language options. Although the application is just one part of the whole, it serves as a key entry point for those in need. The ultimate goal was to increase food security for MA residents by making the SNAP application process accessible and approachable for all.

Results

We designed an application that's fully compliant with WCAG and 508 accessibility standards (archived link, accessed Oct 2018) – and is currently in use in Massachusetts. This work was highlighted in the third edition of Measuring the User Experience by Bill Albert and Tom Tullis.

Time: 2 designers for 12 weeks, 2 engineers for 10 weeks

Tags: Public health & policy

View live appUnderstanding the problem

No one should have to worry about affording their next meal.

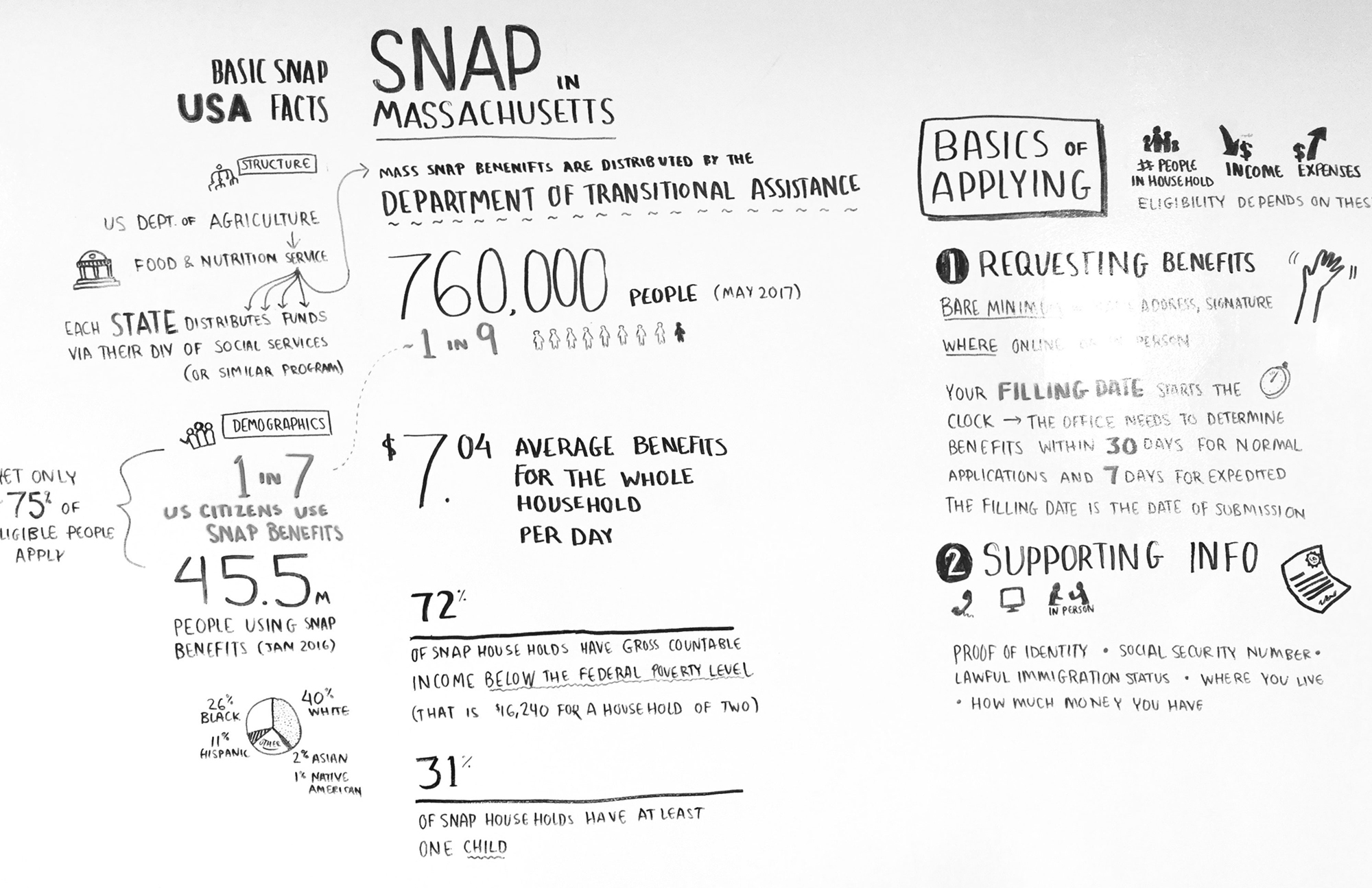

In Massachusetts, the Department of Transitional Assistance (DTA) helps nearly 800K residents afford food every month through SNAP2. Formerly known as Food Stamps, SNAP provides households with anywhere from $15 to $352 per month for a family of two. The DTA reports that “every dollar in new SNAP benefits results in $1.80 in total economic activity.”

Applying for and retaining support is paperwork-heavy

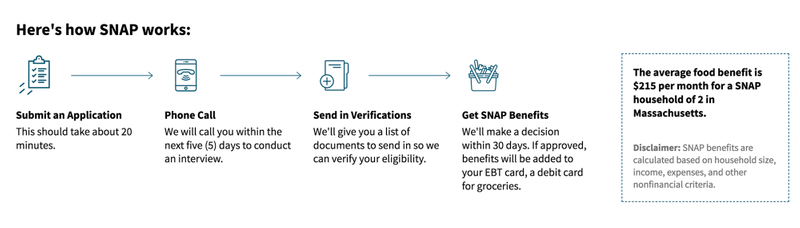

Even if a family has recognized their need and decided to look into options, the application pipeline is time-consuming and emotionally taxing. There are three primary steps to receive SNAP benefits:

- Answer questions about your household

- Perform a phone interview

- Submit paperwork to verify your answers

After eventually receiving benefits, snail-mail and recurring paperwork are a large part of retaining the monthly support.

User driven design

To reach our users most effectively, we spent time gathering information about those applying. We also immersed ourselves in the current state of SNAP locally and nationally. We gathered demographic data and reviewed research about designing government services for those of all language, age, skill, and stress levels.

Before the project began, we reached out to a colleague who had received SNAP benefits as an Americorps teacher (in certain regions, Americorps teachers are encouraged to apply to SNAP). Talking with her put a face to the project and shed light on a teacher’s perspective of SNAP.

We reached out to national experts on SNAP policy and civic design for guidance and design feedback. Through Dana Chisnel, Co-Director of Center for Civic Design, the mantra of the design became “linear and literal.”

We shadowed case workers performing phone interviews and assisting applicants and administrators with their paperwork at the DTA field office in Salem. It was easy to see the stress, language barriers, and confusion that many applicants had throughout this process, which drove us to design the application to be as friendly and streamlined as possible.

Why mobile first makes sense

The Pew Research Center reported that 77% of U.S. adults owned smartphones as of January 10, 20183. Americans making less than $30,000 per year came in at a 67% ownership rate. While residents can access desktop computers at local libraries, many of those who would apply to SNAP have more immediate access to smartphones rather than desktop computers. Having a phone connects people to work opportunities and is a necessity in the modern world.

The process

Re-phrasing and re-organizing application text was critical to the design

Although not originally tasked with updating the questions in the application, we took the initiative to drastically improve the experience. Immediate culprits stood out to us outsiders, such as questions phrased in an accusatory tone, two-in-one questions, lengthy help text, and the sheer quantity of questions. Policies and politics drove the phrasing decisions, heaping on additional complexity. The policy team at the DTA worked tirelessly with us to move the dial on the application questions and help text.

Not all of our efforts made the cut. Accommodating genders beyond the limited ‘Male or Female’ was not an option. Although the whole team could understand how this question may inhibit people from applying, the question couldn’t be changed because it was tied to ingrained processes behind the scenes.

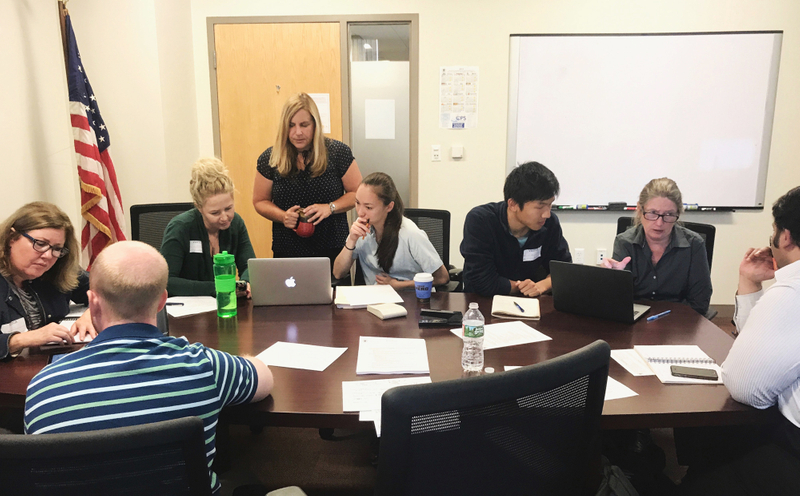

Honing our approach

Design isn’t limited to what the design is but also how the design happens. As weeks went by, it became more difficult to gather detailed feedback from all of those involved who often had diverse perspectives. We found a way to foster rich discussion and capture each person’s perspective by building a prototype of the SNAP application design and spending our meeting time in small groups. We pulled in laptops, iPads, and mobile phones of various sizes, giving everyone time to explore the design on their own. We focused on key questions in small groups and sometimes brought handouts to gather the response of individual members. This change in strategy propelled the design forward and gave us rich feedback from our client and stakeholders.

Delivering on time

Behavior, interactions, feedback loops, and accessibility standards all ultimately manifest in code. To best communicate how the software should perform, we created a reference implementation of the user interface for our engineering partners at Conduent. We built a fully functioning sandbox in React as well as many of the front-end components used in the production environment. Throughout the production cycle, we consulted and QA’ed for the engineering effort, providing supporting materials such as outlines for browser and accessibility testing.

Solution

Simple and accessible

The design is optimized for screen readers, maintains WCAG 2.0 AAA contrast levels, and allows the user to translate the application. The streamlined format minimizes visual burden and reduces missed information.

Reduced question fatigue.

We grouped questions by topic into bite-sized sections, helping users work through the application more efficiently and with less confusion. We decreased the number of questions from about 90 to 40 (estimate for a household of two). The redesigned application uses logic as the user begins answering questions to filter out irrelevant questions.

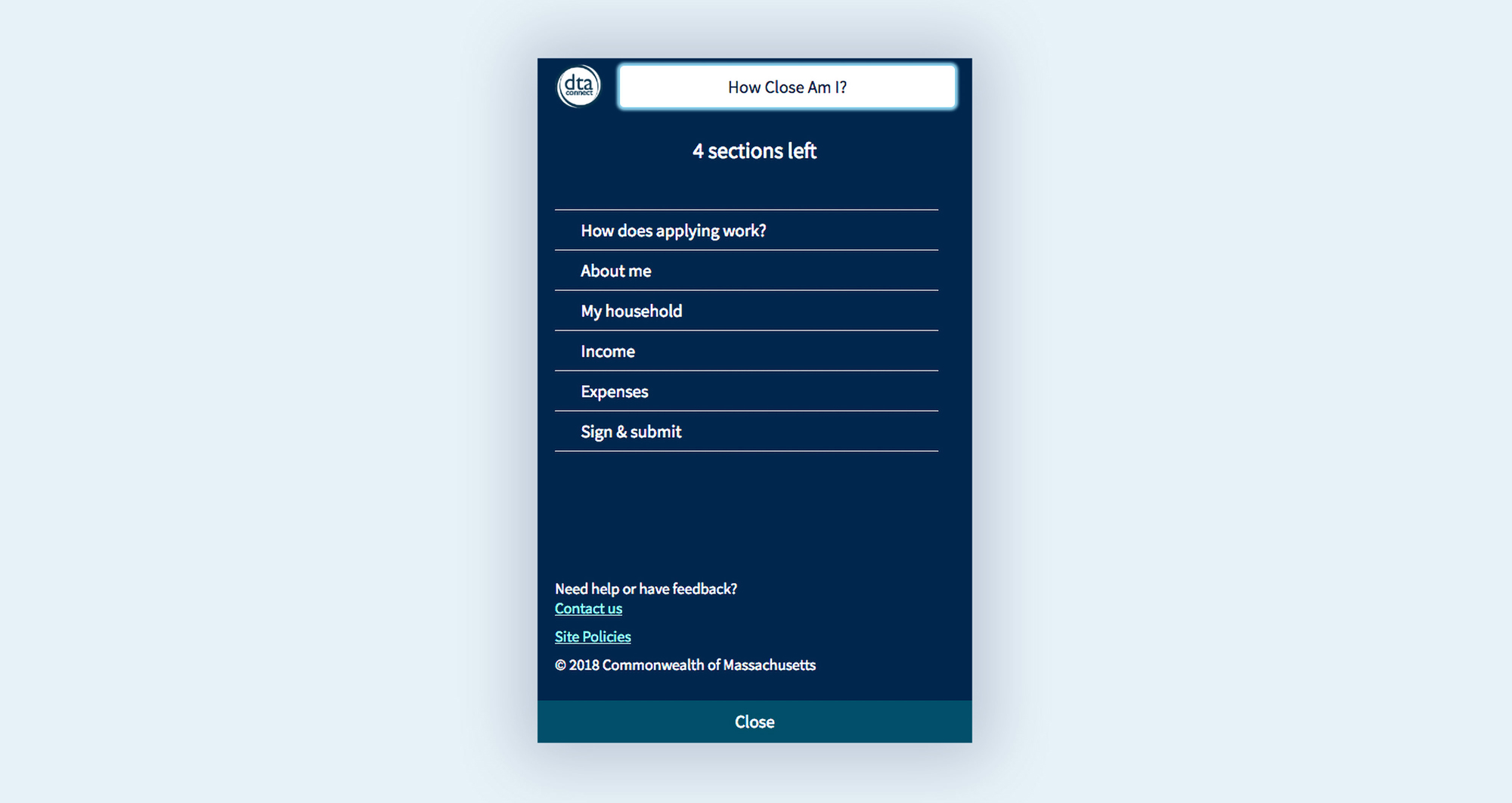

Contextual help

Diagrams at the beginning and end of the application help the user anticipate what comes next. The user gets a chance to catch mistakes through summaries at the end of sections. Definitions and help text expand inline for easiest reading. The user can track their progress in the menu, as it doubles as a checklist.

Results

The redesigned application was deployed in July 2018, and for the first time ever at the MA DTA, the volume of online applications exceeded that of applications completed in person.

Up next

References

- Project Bread Financials & Reports: http://www.projectbread.org/get-the-facts/reports-and-studies/

- 2017 Facts and Figures - December xls report: https://www.mass.gov/lists/department-of-transitional-assistance-facts-and-figures#2017-facts-and-figures-

- Pew Mobile Fact Sheet: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/